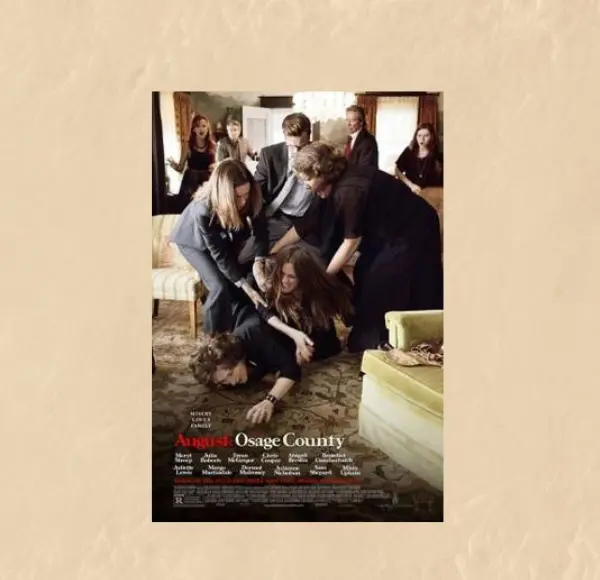

August: Osage County accomplishes a task made exceedingly difficult by its crossing of mediums – it converts an award-winning stage play into an actually engaging two-hour film. True to its theatrical nature, it’s, by necessity, several rooms full of interrelated characters arguing about an agreed-upon and slowly revealed backstory, in which the three most exciting pieces of action include a brief grappling match, an implied suicide and one scuffle with a shovel. Despite this, the film remains an entertaining exercise throughout, though the pacing tends to drag towards the middle. This is accomplished chiefly on the strength of both the film’s source material and the strength of the cast’s performances, though it doesn’t escape wholly unscathed.

In Oklahoma’s eponymous Osage County, the unexpected disappearance and eventual suicide of the Weston family’s patriarch, Beverly (played briefly by Sam Shepard), summons all of its scattered and disparate members to the family’s decrepit home and once again within reach of Violet Weston (Meryl Streep), their cancer-ridden, drug addict mother. Their three daughters – Barbara (Julia Roberts), Karen (Juliette Lewis) and Ivy (Julianne Nicholson) – each arrive for the funeral, trailing their own respective lives, families and baggage. The results of mixing all ten of these personalities under Violet’s roof forms the crux of the film’s drama.

The screenwriter and the playwright are thankfully the same person – Pulitzer Prize-winner Tracy Letts – making the adaptation that much more effective. One assumes that entire scenes are lifted, whole cloth, from the stage play and the dialogue crackles as a direct result, the screenplay the other of the film’s two great strengths. The pacing becomes somewhat confused approximately three-fourths of the way through, in which the character of Violet all but disappears from the film for a solid, ten-minute to twenty-minute block, in order to resolve the gaggle of subplots that’ve been brewing in the background. One of the most interesting themes addressed in the film is its focus on the women in the family as the dynamic movers-and-shakers, whereas the men they’ve attached themselves to are primarily treated as passive accessories. It’s refreshing to see a realist drama that concentrates almost solely on the plight of modern women, rather than modern men.

As to be expected, the cast of the film is its universal praise point. Streep and Roberts are the two performances we’re meant to laud, the former showing her typical range of incredible emotion and complexity and the latter displaying an unseen level of intensity, but the supporting cast is where much of the true magic lies. A primary subplot, centered on the youngest daughter Weston and Violet’s sister Mattie Fae (Margo Martindale) features two of the film’s most exceptional and unnoticed performances; Chris Cooper as Charles, Violet’s humble and long-suffering brother-in-law, and Benedict Cumberbatch as his son, Little Charles, a doddering buffoon whose only redeeming character trait seems to be his earnestness.

The source material owes a tremendous debt to the American realist dramas of the 1930s, particularly those of Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams, in which scenes are confined to a small spread of rooms within the Weston house. The film subverts this somewhat, with the director’s choice to plant some scenes in surrounding areas; a police man’s car, a parking lot within the local small town, a screened-in porch on the Weston property. Otherwise, the director’s hand is practically unseen the entire film, John Wells wisely deciding to remain sensibly invisible in light of this juggernaut cast.

In short, the film pulls off its balancing act of good acting, good writing and invisible direction, though it’s clear that too much prodding in either direction could collapse the entire thing into a wordy mess.